Comprehensive CPT Code Directory for Surgery Procedures

CPT coding for surgery is the backbone of revenue cycle accuracy in surgical practices, ambulatory surgical centers, and hospital ORs. Yet, miscoding remains a top driver of denials, clawbacks, and compliance audits in 2025. The complexity of bundled surgical codes, modifier use, and anatomic subdivisions across multiple specialties makes this area a minefield for both new and seasoned coders. With payer scrutiny intensifying, even a minor error in assigning or sequencing codes can mean thousands in lost reimbursement—or worse, payer investigations.

This directory is your high-precision reference for surgical CPT coding. Designed for medical coders, billing professionals, and audit reviewers, it goes beyond textbook definitions to map real-world claim patterns, code relationships, and evolving payer edits. Whether you're preparing for a certification exam or tackling high-volume surgical claims, this guide gives you the clarity and depth to code confidently, minimize denials, and stay ahead of 2025's coding shifts.

CPT Code Structure for Surgery

Category I Codes and Surgery Chapter Layout

CPT’s surgical section is structured within Category I codes, spanning the 10021–69990 range. These codes are organized not by specialty, but by anatomic region and procedural type, making it essential for coders to understand the logic behind the sequence. The CPT manual begins the surgery chapter after the Evaluation & Management (E/M) section and breaks it into systematic groupings for faster code retrieval and documentation alignment.

Each section includes parenthetical instructions, guidelines on appropriate reporting, and modifier applications. For instance, code 19301 (partial mastectomy) includes key instructions on tissue margins and specimen orientation, which directly affect claim accuracy and compliance audits. CPT's structure ensures consistency across payers, providers, and facilities, but only if coders interpret the framework precisely.

Subsections of Surgery by Anatomic Region

CPT surgery codes are divided into organized body systems, allowing coders to navigate procedures logically. Each major subsection addresses a different anatomic or functional system:

Integumentary System (10021–11983)

Includes biopsies, excisions, repairs, and skin grafts.

Musculoskeletal System (20000–29999)

Covers open, percutaneous, and endoscopic orthopedic procedures.

Respiratory System (30000–32999)

Spans procedures from nasal sinus work to thoracotomy.

Digestive System (40000–49999)

Covers endoscopy, GI repairs, and complex resections.

Urinary and Male Genital Systems (50000–55899)

Includes nephrectomy, prostatectomy, and catheterization procedures.

Female Genital and Maternity Care (56405–58999)

Encompasses hysterectomy, cesarean sections, and related services.

Nervous System (61000–64999)

Covers brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerve surgeries.

This structure supports clean claim submission by encouraging correct code sequence based on anatomic hierarchy rather than provider specialty.

Use of Modifiers in Surgical Coding

Modifiers play a critical role in refining CPT codes for surgical claims. Modifier 51 (Multiple Procedures) is used when more than one surgical procedure is performed at the same session. Modifier 59 (Distinct Procedural Service) signals a separately identifiable service not typically reported together. Modifier 78 indicates an unplanned return to the OR for a related procedure.

Example 1: 23410 (repair of rotator cuff) + 29826 (arthroscopic subacromial decompression). To prevent bundling edits, coders may use Modifier 59 on 29826 if documentation supports it.

Example 2: 47562-78 (laparoscopic cholecystectomy, return to OR for bleeding control). Modifier 78 tells the payer it’s a related procedure during the global period.

Precise modifier use ensures reimbursement accuracy, prevents denials, and reflects procedural intent as documented.

| System | Code Range | Includes |

|---|---|---|

| Integumentary System | 10021–11983 | Biopsies, excisions, repairs, grafts |

| Musculoskeletal System | 20000–29999 | Orthopedic procedures (open, percutaneous, endoscopic) |

| Respiratory System | 30000–32999 | Sinus work, bronchoscopy, thoracotomy |

| Digestive System | 40000–49999 | GI repairs, endoscopy, complex resections |

| Urinary & Male Genital Systems | 50000–55899 | Nephrectomy, prostatectomy, catheterization |

| Female Genital & Maternity Care | 56405–58999 | Hysterectomy, cesarean sections, OB services |

| Nervous System | 61000–64999 | Brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerve surgeries |

Top CPT Coding Rules for Surgical Claims

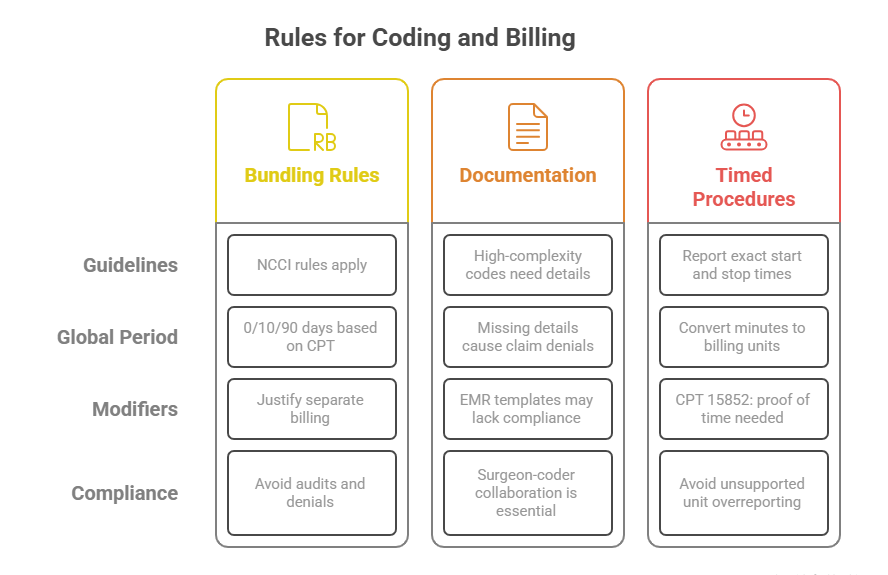

Bundling and Global Surgical Package Rules

Surgical coding goes far beyond picking a standalone CPT. Many procedures are subject to bundling rules under the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI), which prohibit billing certain services together unless documentation supports modifier use. Coders must assess whether components of a procedure—like lysis of adhesions or debridement—are included in the global surgical package, which spans pre-op, intra-op, and post-op phases.

The global period can last 0, 10, or 90 days, depending on the code. For instance, excision of skin lesions typically has a 10-day global, while a total knee arthroplasty has a 90-day window. Billing for follow-up visits or related procedures within this timeframe requires careful application of modifiers like 24 (unrelated E/M) or 78 (return to OR).

Knowing when two codes violate bundling edits—versus when they qualify for distinct reimbursement—is essential to avoiding denials and audits.

Documentation Requirements for Complex Codes

High-complexity surgical codes require equally detailed documentation. Without operative notes that explicitly cover anatomic site, surgical technique, instruments used, and intraoperative findings, many claims risk downcoding or rejection. For example, CPT 22558 (lumbar spinal fusion) requires proof of approach, fusion technique, and grafting method.

Payers increasingly demand intraoperative details, especially for high-RVU procedures. Templates and EMR auto-fill notes often fall short of proving medical necessity. Surgeons and coders must collaborate to ensure the documentation reflects not just what was done, but why, how, and where.

Even with the correct CPT selected, lacking specificity in op reports (e.g., missing laterality or exact site) can render the code unbillable or trigger payer requests for additional records.

Timed Procedures and Multiple Units Reporting

Some surgical services—like debridement, anesthesia adjuncts, or physical therapy during wound care—are time-based codes. These require exact start and stop times documented in the operative note. For instance, CPT 15852 (dressing change under anesthesia) must reflect total anesthesia time and medical necessity.

Coders must convert total minutes into billable units and report them accurately. A 45-minute procedure billed under a 15-minute increment code (e.g., 97140 for manual therapy) justifies 3 units, not 1. Many denials stem from over-reporting units without documentation support.

For surgical coding, clarity on units, modifiers, and time-based structure is crucial. It’s one of the most common areas flagged during post-payment audits by CMS and commercial payers alike.

Surgical Procedure CPT Code Directory

Below is a high-utility CPT directory rable covering essential surgery procedure codes. This is structured to support coders in fast lookups by anatomic category, frequently billed procedures, and typical use cases. The selections reflect high-volume codes across specialties and those prone to denial or bundling issues.

Note: This directory is not exhaustive but curated for real-world use across hospital, outpatient, and ASC settings.

| CPT Code | Description | Common Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 11400 | Excision, benign lesion, trunk/arms/legs; excised diameter 0.5 cm or less | Removal of small skin growths |

| 19301 | Mastectomy, partial (e.g., lumpectomy) | Breast cancer treatment |

| 23410 | Repair of ruptured musculotendinous cuff (e.g., rotator cuff) | Shoulder tear reconstruction |

| 29827 | Arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; with rotator cuff repair | Minimally invasive shoulder surgery |

| 33533 | Coronary artery bypass, using arterial graft(s); single arterial graft | Cardiac revascularization surgery |

| 47562 | Laparoscopy, surgical; cholecystectomy | Gallbladder removal |

| 50590 | Fragmenting of kidney stones using lithotripsy | Kidney stone treatment |

| 52235 | Cystourethroscopy with removal of small bladder tumor(s) | Urology outpatient surgery |

| 58661 | Laparoscopy, surgical; with removal of adnexal structures (partial or total) | Ovarian cyst or tube removal |

| 63030 | Laminectomy with decompression of spinal nerve root | Spinal stenosis or disc herniation |

| 66984 | Extracapsular cataract removal with insertion of intraocular lens | Routine cataract surgery |

| 69631 | Tympanoplasty without mastoidectomy | Repair of ear drum perforations |

Common Coding Errors in Surgery Billing

Upcoding, Unbundling, and Incomplete Coding

Three of the most frequent—and costly—errors in surgical billing are upcoding, unbundling, and incomplete coding. Upcoding occurs when a more complex or higher-paying code is selected than documentation supports. For example, choosing CPT 23412 (extensive rotator cuff repair) instead of 23410 (limited repair) without clinical justification will raise payer red flags and invite audits.

Unbundling is when components of a single surgical service are reported separately, despite being part of the global CPT. For example, billing 47560 (diagnostic laparoscopy) along with 47562 (laparoscopic cholecystectomy) without a modifier will trigger bundling edits—since the exploratory part is already included.

Incomplete coding, on the other hand, happens when supporting codes (e.g., anesthesia, assistant surgeon, or device codes) are missed. This results in under-reimbursement and weak documentation trails, especially during RAC or MAC audits.

Avoiding these errors depends on coder education, up-to-date references, and solid documentation workflows.

Missing Documentation for Assistant Surgeon or Co-Surgeon

When surgical claims involve an assistant surgeon (Modifier 80) or co-surgeon (Modifier 62), detailed documentation is critical. Many coders forget to include supporting evidence like op notes stating the role of the assistant, their unique contributions, or the medical necessity of their presence. Payers may deny these line items even if the coding is technically correct.

Some carriers only approve assistant billing for specific CPT codes. For example, many cosmetic procedures don’t justify an assistant unless complications arise. Without this validation, reimbursement for assistant roles is routinely denied.

To avoid this, coders must use CMS assistant-at-surgery indicators, validate payer-specific policies, and ensure the surgeon explicitly documents the need for support during the procedure. Failure to do so can result in denied claims or flagged audits that question the billing integrity of the entire case.

Issues with Post-Op Follow-Ups Inside Global Period

Follow-up care within the global surgical period (10 or 90 days) must be coded with surgical context in mind. Coders sometimes bill routine post-op visits as E/M codes without a Modifier 24 (unrelated visit) or Modifier 25 (significant, separately identifiable E/M). This misstep leads to denials and makes claims vulnerable to post-payment review.

For instance, a patient returning after total knee replacement for incision evaluation cannot be billed separately—it’s included in the surgical package. However, if the patient comes in for an unrelated GI issue, Modifier 24 is needed to process the claim correctly.

Coders must review each encounter within the global window and confirm whether it’s routine, related, or separately payable. Good EMR note structuring and team communication are vital to prevent these repeated revenue leaks.

Tools and Databases for CPT Code Accuracy

EncoderPro, AAPC Coder, SuperCoder

Even expert coders can miss a bundling rule or modifier nuance without the right digital tools. EncoderPro by Optum, AAPC Coder, and SuperCoder (now part of Find-A-Code) are leading platforms that offer real-time access to the most current CPT, ICD-10, HCPCS, and NCCI edits. Each tool supports code lookups, CCI bundling alerts, and documentation tips.

EncoderPro offers customizable code books, while AAPC Coder integrates direct guidance from AAPC forums and CEU resources. SuperCoder excels in specialty widgets like modifier crosswalks and audit risk indicators. Coders working with high-volume surgical claims benefit most from tools that crosswalk CPTs to ICD-10s and flag outdated or denied pairings instantly.

Failing to use a live-coded database in 2025 risks pulling outdated codes—a leading cause of payer denials and medical necessity mismatches.

NCCI Edits and MUE Tables

The National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) and Medically Unlikely Edits (MUEs) are foundational datasets coders must check before submitting surgical claims. These databases, published by CMS and adopted by most private payers, define what code combinations are allowable and how many units are realistically payable.

NCCI bundling edits flag scenarios where two CPTs shouldn’t be billed together unless documentation supports the use of a modifier. MUE tables help prevent overbilling of code units—for example, trying to report CPT 11730 (nail avulsion) more than once per toe or day.

Example: Coding 47562 (lap cholecystectomy) with 49320 (lap diagnostic procedure) without Modifier 59 will be denied—NCCI recognizes this as bundled unless clearly justified.

Checking these databases ensures coders don’t trigger rejections or risk accusations of intentional overcoding. Top coders integrate these tools into their daily workflow, not just audits.

Recent CPT Surgery Code Changes for 2025

Revised and Deleted Surgical Codes in AMA 2025 Manual

Each year, the AMA revises CPT codes to reflect evolving surgical techniques, medical device innovations, and payer alignment. In 2025, several high-use surgical CPT codes were either revised for clarity or deleted due to obsolescence. These changes directly affect claim accuracy, especially if outdated codes are submitted after January 1st.

For example:

22869 (interbody fusion using posterior approach) was revised to reflect graft technique documentation.

19303 (mastectomy, simple, complete) received guideline changes around tissue reporting.

28122 (partial excision of tarsal/metatarsal bone) was deleted due to redundancy with 28120 and 28124.

Coders relying on templates or macros must ensure their coding libraries reflect these changes, or risk a denial for using invalid or outdated codes. Every CPT update must be crosschecked with payer bulletins and clearinghouse rejections to align with accepted claims logic.

Payer-Specific Changes and Billing Guidelines

Beyond AMA-level changes, commercial payers and CMS release quarterly edits that coders must track. In 2025, several payers updated rules around assistant surgeon use, bundled lab/pathology services during surgery, and prior authorization triggers.

Examples of key 2025 payer shifts:

UnitedHealthcare revised its bundling logic for GI endoscopy codes to match CMS edits.

Blue Cross Blue Shield disallowed assistant-at-surgery (Modifier 80) for several minor ENT procedures unless intraoperative complications are documented.

CMS added stricter documentation thresholds for high-RVU spinal fusion codes like 22633 and 22634.

Coders and revenue cycle teams must monitor both AMA CPT updates and payer-specific policies in tandem to prevent surprise denials and ensure clean claim submissions. Tools like CPT Assistant and payer policy archives should be part of every coder’s workflow.

How Our Medical Coding Certification Helps You Master Surgical Codes

Deep CPT Coverage in AMBCI’s Medical Billing and Coding Certification

Surgical coding isn’t just about memorizing procedure codes—it’s about understanding documentation logic, modifier application, and payer-specific nuances. The Medical Billing and Coding Certification program by AMBCI goes beyond generic instruction to equip learners with precision coding skills for surgery-heavy claims.

Inside the program, learners are trained to master:

Global period structures across surgical specialties

NCCI bundling logic and modifier 59 usage

Real-world operative reports with hands-on CPT assignments

Every lesson is built with practical case-based scenarios that reflect the complexities of today’s coding audits. Whether you’re billing for orthopedic procedures, GI interventions, or OBGYN surgeries, you’ll leave the course knowing how to code each case for maximum compliance and reimbursement.

200+ Modules Including Surgery Subspecialties

The program includes 200+ modules, many of which are dedicated to surgical subspecialties like:

Cardiothoracic surgery

Neurosurgery

Ambulatory laparoscopic procedures

Minor integumentary and ENT codes

These are not surface-level overviews—they dive into:

Modifier sequencing (e.g., 58 vs 78 vs 79)

Surgical anatomy coding logic

Carrier-specific denials and appeals

Every learner has access to up-to-date CPT guidelines, curated examples, and specialty-specific coding toolkits. This depth ensures you're not only exam-ready but audit-proof, making you an asset to employers in hospitals, ASC groups, and billing firms alike.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

The most frequently used CPT codes for general surgery include 47562 (laparoscopic cholecystectomy), 44950 (appendectomy), and 49505 (inguinal hernia repair). These codes represent high-volume, routine procedures in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Surgeons and coders must also watch out for commonly bundled services like 47560 (diagnostic laparoscopy), which cannot be reported separately with 47562 unless modifier 59 is properly applied. Understanding global periods, payer edits, and NCCI bundling restrictions is essential for each of these high-usage codes. Coders should also stay current with annual updates, as even frequently billed codes can face description changes or documentation shifts.

-

To check if a CPT code is bundled with another, consult the NCCI (National Correct Coding Initiative) Edit Tables published by CMS or use commercial tools like EncoderPro and AAPC Coder. These databases show which CPT codes are considered mutually exclusive or column 1/column 2 pairs, meaning one is included in the other and shouldn’t be billed separately. If a modifier like 59 or XS can be used to override the edit, the tool will indicate it. Bundling errors are a top cause of denials and audits, so coders must cross-check before submitting any multi-procedure surgical claim.

-

When reporting multiple surgical procedures performed during a single operative session, you typically use Modifier 51 (Multiple Procedures) for the secondary codes. Modifier 51 tells payers that the procedures were distinct but performed together. The highest-valued procedure is listed first (without the modifier), and subsequent procedures receive the modifier and are paid at a reduced rate. In cases where procedures are unrelated or occur on separate sites, Modifier 59 or XS may be more appropriate to denote separate anatomical regions or procedures. Correct modifier selection affects both reimbursement and audit safety.

-

Modifier 78 is used when a patient returns to the OR during the global period for a related surgical procedure, such as complication management. It indicates the service is part of the original surgical episode but required further intervention. Modifier 79, on the other hand, is used when the patient returns for an unrelated procedure during the global period. For example, if a patient had a hernia repair and returns a week later for excision of a skin lesion on the back, Modifier 79 applies. Choosing the wrong one can result in rejected claims or incorrect payment.

-

Surgical coding uses procedure-based CPT codes, usually from the 10021–69990 range, and includes considerations like global periods, anesthesia status, and modifier use. E/M (Evaluation and Management) coding, in contrast, is visit-based and driven by medical decision-making or time spent. In surgical cases, coders must determine whether the E/M visit is billable separately from the procedure—especially within the global period. For example, a post-op visit is generally not separately reportable unless it's for an unrelated issue and supported by Modifier 24. Surgical coding involves more documentation rules and bundling considerations than E/M coding.

-

Key tools that reduce surgical CPT errors include AAPC Coder, EncoderPro, SuperCoder, and CMS’s NCCI Edits and MUE tables. These tools flag incompatible code combinations, modifier misuse, over-reporting of units, and outdated codes. Many platforms also include payer policy databases to ensure claims are aligned with individual insurer guidelines. Coders can integrate these tools directly into their workflow or EHR system for real-time decision support. Routine use of these platforms prevents denials, supports audit-proof claims, and improves revenue cycle integrity for surgical departments. Manual lookups alone are no longer sufficient in 2025’s audit environment.

-

Surgical CPT codes are updated annually by the AMA, typically with changes released in the fourth quarter of the preceding year. These changes include new codes, revised descriptions, and deleted procedures. Additionally, CMS and commercial payers issue quarterly policy updates that may impact code coverage, modifier requirements, or prior authorization rules. Coders must stay current by subscribing to CPT Assistant, payer bulletins, and coding newsletters. Using outdated CPT codes—especially for high-RVU procedures—can result in claim denials, compliance flags, and lost revenue. Staying updated is a core competency for surgical billing professionals.

The Take Away

Surgical coding isn’t just another chapter in the CPT manual—it’s the most complex, audit-prone, and revenue-critical domain in medical billing. Errors in this area account for a disproportionate share of claim denials, reimbursement delays, and compliance investigations. From understanding how surgical codes are structured across body systems to properly applying modifiers and respecting global period rules, mastery requires both technical depth and tool-based precision.

Whether you're working in a hospital, ASC, or third-party billing firm, the stakes are high. The wrong code—or even the right code submitted without documentation support—can result in massive financial loss or payer scrutiny. That’s why coders equipped with formal certification and hands-on CPT training outperform those relying solely on experience.

With this guide and the right credential—such as AMBCI’s Medical billing and coding certification program—you gain a surgical coding skillset built for 2025’s payer landscape. Precision, speed, and compliance are no longer optional. They’re the foundation of sustainable success in the modern revenue cycle.

Poll: Which aspect of surgical CPT coding do you find most challenging?